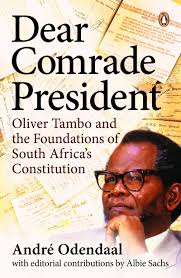

Oliver Tambo was teacher, political leader, diplomat and revolutionary. As Deputy President and later President, he led the African National Congress in exile for 30 years, while Nelson Mandela and many others were gaoled in South Africa. Under Tambo’s leadership, the ANC’s external mission grew from a few exiles into a movement with once’s in all the world‘s major capitals. From the mid-1970s it inspired, and built links with, the mass movement against apartheid inside South Africa. Tambo held the ANC together, seeking consensus, but never afraid to take difficult decisions. He was a strategic thinker, who endorsed the decision to pursue armed struggle in 1961, and in the 1980s seized the chance for negotiations with the apartheid regime. Tambo was respected by world leaders and inspired hundreds of thousands of people to join the antiapartheid struggle. This exhibition tells how he crossed ideological and geographical boundaries, building a truly global movement.

Oliver Reginald Tambo, leader of the African National Congress in exile for thirty years, died on 23 April 1993. Yet his legacy lives on. Comrade O.R. left us a significant and enduring heritage, one, which enhanced our new constitution, contributed to the inclusive and equitable policies of our democratically elected government, and affirmed the abiding vision of the ANC itself.

The African National Congress has consistently produced leaders of the highest calibre. But Oliver Tambo, thoughtful, wise and warmhearted, was perhaps the most loved. His simplicity, his nurturing style, his genuine respect for all people seemed bring out the best in them. Comrade O.R.’s life was remarkable for the profound influence he had on the ANC during the difficult years of uncertainty, loneliness and homesickness in exile. During his fifty years of political activity in the ANC, Comrade O.R., as he affectionately came to be known, played a significant role in every key moment in the history of the movement, until his death. Oliver Tambo is a founder member and secretary of the ANC Youth League in 1944; the general secretary of the ANC from 1952; the mandated leader of the ANC’s Mission in Exile 1960; the President of the ANC from 1977 until 1990; then National Chairperson until his death, in 1993.

What shaped the life of Oliver Tambo? What values and life skills enabled him to make such an important and enduring impact on the history of the African National Congress and on our new, democratic South Africa? Two major processes in Comrade O.R.’s early life moulded his style in politics and leadership – his traditional rural roots; and the expertise he acquired through education. Each experience was very different; yet O.R. combined them creatively to develop an approach, which was able to reach and empower a broad mass of the people, both nationally and internationally.

On an early summer morning on 17 October 1917, in the small village of Kantolo, about 20 kilometres, from Bizana, Pondoland, a son was born to Mzimeni, son of Tambo, and his third wife, Julia.

Pondoland, known for its green, fertile and available land, had been the last chiefdom in South Africa to remain independent. The annexation of Pondoland had taken place within Oliver Tambo’s parents’ lifetime. It was an act that completed the process of colonial dispossession of South Africa. Tambo’s father was acutely conscious of this British assault on Pondoland; the naming of his son ‘Kaizana’, after Britain’s enemy, the Kaizer of Germany during World War One, was making a pointed statement.

The Tambo homestead was unusually large:’ a big kraal, as distinct from a two-hut home, of which there were many’, remembered O.R. The homestead consisted of the paternal grandparents, their three sons, and their wives and children. Oliver’s father, Mzimeni, who was not a Christian, had four wives (though he married his youngest wife, Lena, only after his second wife died in labour). It is a tribute to Mzimeni that family relationships were harmonious. The wives had an excellent relationship, and the ten children were very close. Mzimeni was comfortably off. He owned at least 50 cattle at one time, several fine horses and an ox-wagon. These resources led to trading and transport opportunities. Mzimeni was not literate – ‘my father had not seen the inside of a classroom’. His prosperity was largely due to his own enterprise. Shrewd, creative and quick to seize an opening, Mzimeni sought and gained employment as an assistant salesman at the nearby trading store. This exposure to a more commercial economy taught Mzimeni a number of skills and widened his world.

Two women in O.R.’s life, his own mother, and his father’s third wife were Christians. They also opened up new horizons. Oliver’s mother was a sociable and energetic person who could read and write. She established her home as the local headquarters of the Full Gospel Church. Tambo recalled occasions when there were large, bustling gatherings of worship in his mother’s hut. Eventually, perhaps because of her influence, Mzimeni himself converted to Christianity, and had all his dependents baptised.

In that somewhat large and busy homestead, Kaizana had an active, happy and traditional childhood. From as early as three or four years old, young Kaizana was learning the essential skills of the rural economy, and the practical discipline that went along -with it. Tambo vividly recalled the duties of the small boys, describing their fairly heavy responsibilities in tending the calves, and ensuring that the animals were permitted to suckle only after milking. As the boys grew older and were able to accept more responsibility, they were given the task of herding the cattle.

The young Tambo took pride in taking responsibility for more grown up tasks. He learnt to plough; He mastered the difficult craft of spanning a team of oxen. He taught them to obey commands ‘in such a way as the whole team pulls together’.

The whole family contributed to the homestead economy. Work was practical and rewarding. Unlike labour in industrial society, it was not separated from home or community. Herding, like other productive activities, would be done in groups, and would include social interaction and cooperation.

In a society where everyone knew almost everyone else, group pressure was a strong form of discipline. The Amapondo like many polities in southern Africa, had a consensus approach to decision-making. Between headmen and the community, as well as between chiefs and the people, there was a balance of power. In his autobiography. President Mandela recalled how ‘at a council meeting, or imbizo, everyone was heard: chief and subject, warrior and medicine man, shopkeeper and farmer, landowner and labourer… It was democracy in its purest form’.

After thorough discussion, the chief and his advisers would get the feel of the meeting. Opponents of the plan were encouraged to speak out. Chiefs relied on their councillors to prevent them from acting contrary to popular will. This very sound practice, of never straying too far away from their constituencies – was to play a profoundly important role in the ANC style of leadership of both Tambo and Mandela By the time little Kaizana was old enough to herd, a cash economy had already begun to infiltrate the area. Regularly, young men from Kantolo would take the 25-kilometre trip to Bizana, where there was a recruiting station for the coalmines in KwaZulu-Natal and the gold mines in Gauteng, in order to earn money for taxes. All of Oliver’s older brothers became wage labourers, both the traditionalists, such as Willy and Zakele, and the younger Christians such as Wilson and Alan. The migrant labour system was indeed an integral part of the homestead economy, and became Migrant labour also brought risk and adversity. The health of Wilson, Oliver’s older brother, was ruined when he contracted TB in the compounds of the sugar plantations and had to return home, permanently unfit for strenuous work. In about 1929, the Tambo family suffered a major tragedy: Oliver’s uncle and his older brother Zakele were killed in an underground fire in the Dan Hauser coal mine. Aside from the heartbreak and personal anguish, the deaths of two healthy and productive members of the homestead was a severe economic blow, and further hastened the until the end of his life, Oliver Tambo remained deeply attached to his traditional culture. But, thanks to the shrewd insight of his father, O.R. was also able to learn the skills of the colonisers.

Although Mzimeni Tambo was a traditionalist, he also saw the value of western education. Working in the trading store for many years, Mzimeni had been impressed by two aspects of the white trader: that his learning enabled him to run an independent business and keep its books; and that his relative wealth gave him power and status. As Comrade O.R. observed:

People went to him to buy. He had a car, horses – he was a reference point to the community – and he had servants. In general he was a chief in his own right. He certainly was something above the level of ordinary people. It was exactly this difference of levels that my father was targeting, in insisting that his children should go to school.

On his first day, young Kaizana was asked to come to school with a new, ‘English’ name. After his mother and father discussed it at length that evening, the little boy took his new name to his teacher. It was, he said, to be ‘Oliver’. The schoolteacher turned out to be very strict, and would beat the children for the slightest offences. Oliver began to dread school, and would find any excuse not to take the long ten-mile walk to school. Mzimena was so determined that his children should persevere that he moved the children several times to other schools. As he grew older, Oliver began to want to leave home.

My age group, some of them, had left their homes, crossed the Umtamvuna and went to Natal to work – some in the plantations. And some were coming back, big stout chaps already. They were young men, and I was still going to this school. So I began to think in terms of leaving, escaping to go and work there as a garden boy or even in the sugar plantations. I would work there and bring back money to my parents – that’s what everyone else was doing.

One day, when Oliver was about eleven years old, he met a lad who was in the debating society of another school. He and his friends were deeply impressed with the ease with which this youngster spoke English. That experience changed Oliver’s attitude to education. He had discovered in himself a love of discussion and debate, and English seemed to be the key to skills, independence and power.

Not long afterwards, Oliver was given the opportunity, through a family friend, to enrol at the missionary school at Flagstaff, called Holy Cross. By this time, Oliver’s father did not have money to pay the fees. But Oliver was so anxious to stay, that the school itself managed to find two kind English sisters who sent the sum of ten pounds a year for Oliver’s schooling. His older brother, working as a migrant in faraway KwaZulu-Natal, also sent an additional amount from his hard-earned wages to make up the shortfall in the fees.

From then onwards, Oliver never looked back. Really motivated to learn now, he starred in class. After five years at Holy Cross, his teachers found him a place in the well-known black school of St Peter’s in Johannesburg. Many years later. Comrade O.T. linked the kind deed of the English ladies to the international support ‘for those engaged in the struggle for liberation from oppression and the apartheid system in particular’ in the years to come.

‘They were total strangers to us as we were to them. They intervened tirelessly to save the careers of two unknown youngsters who but for their intervention, might have bad to say goodbye to Holy Cross and goodbye to education as well as goodbye to a future of possible usefulness to humanity… They bad stretched a couple of bands across the lands and oceans to the south of the continent of Africa to give aid and support to two unknown children. Two unknown African children.’

Oliver finished his schooling at St Peter’s in Johannesburg, a school which exposed him for the first time to boys from other provinces, who spoke other African languages, and also to fast-talking city youngsters. For the first time, in the streets of Johannesburg, he was exposed to race prejudice and segregation but city life was to be his future. Within a year, first his mother and then his father passed away – at the age of sixteen, he was orphaned.

His parents did not live to delight in their son gaining top marks in matric. In those days all scholars in the Transvaal, black and white, wrote the same examination. The black press reported the achievement with great pride that this excellent scholar was from the Transkei, the eastern Cape assembly of chiefs, the Bhunga, granted Oliver a bursary of 30 pounds a year to study at Fort Hare.

Oliver decided to study science. There was an imbalance, he decided, in the black professions there were too many B.A. candidates. Ideally, he had wanted to study medicine; but at the time no university would accept black students. Three years later, Oliver Tambo graduated with a B.Sc. degree in physics and maths. The following year he enrolled for a diploma in higher education. O.T. had a calm and quiet disposition, but he made an impact on his lecturers and his fellow students. He was deeply religious, yet he was also an intellectual. His future friend, partner and comrade, Nelson Mandela, recalled his first impressions of Oliver:

I became a member of the Students Christian Association and taught Bible classes on Sundays in neighbouring villages. One of my comrades on these expeditions was a serious young science scholar whom I had met on the soccer field. He came from Pondoland, in the Transkei, and his name was Oliver Tambo. From the start, I saw that Oliver’s intelligence was diamond-edged; be was a keen debater and did not accept the platitudes that so many of us automatically subscribed to. Oliver lived in Beda Hall, the Anglican hostel, and though I did not have much contact with him at Fort Hare, it was easy to see that he was destined for great things.’ Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom.

Oliver was elected chairperson of the students’ representative council of his Anglican residence, Beda Hall. But before his last year at Fort Hare was through, he was expelled for organising a student protest on a point of principle. He then left the university and went home to Kantolo, planning to look for a job – any job, for he had the younger members of the homestead to support. But the news of his expulsion reached his old school, St Peter’s. They immediately offered him a post as Maths, master.

Once again, Oliver was in Johannesburg, and once again, he was in the news amongst the black community. In downtown Johannesburg near Diagonal Street was an estate agent called Walter Sisulu with an office, which attracted the young black elite – the teachers, lawyers, journalists and intellectuals who loved a good discussion on politics and life. Sisulu was keen to meet Tambo, and in due course, friends brought the brilliant scholar around. Tambo at once took to the slightly older man, who had not had much formal higher education, but was seasoned in the hard knocks of city life and had acquired a wealth of wisdom and political insights. Sisulu was interested in marshalling the abilities of the young people who came to his office in the service of their community. At Sisulu’s office, Tambo met other like-minded young men – Anton Lembede, A.R Mda, Jordan Ngubane as well as a fellow student whom he remembered from Fort Hare – Nelson Mandela.

Nevertheless, they agreed, the ANC was the organisation with a long tradition and my honourable nationalist vision, which they felt they could work with. The group decided on a plan of action to revive Congress. Meeting regularly at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre, they decided to put a resolution to the next annual congress.

In 1944, the ANC Congress in Batho, Bloemfontein formally created the ANC Youth, League, as well as a Women’s League. Anton Lembede was elected chairman, Oliver ambo secretary and Walter Sisulu treasurer of the new organisation.

AFRICA’S CAUSE MUST TRIUMPH’, declared the Youth League manifesto. ‘We believe that the national liberation of Africans will be achieved by Africans themselves… We believe in the unity of all Africans from the Mediterranean Sea in the North to the Indian and Atlantic Oceans in the South… and that Africans must speak with one voice.

The Youth League undertook to provide a three-year programme to mobilise the ordinary black people of South Africa.

In the meantime, Tambo was making an enduring impact on his students at St Peters. Dozens of his students remembered his distinctive, interactive and encouraging style of teaching, using methods, which were well ahead of their time. O.R. inspired many to take up teaching too. After hours, he introduced the concepts of the Youth League to his senior students. Some of them went on to join the movement and become prominent comrades. Amongst them were Andrew Mlangeni, Henry Makoti, Duma Nokwe, Joe Matthews, Vella Pillay and a number of others – although another pupil took a different political direction – Lucas Mangope.

In 1948, the National Party was voted into power by the white electorate. They immediately set about extending and introducing a host of racially discriminating laws. The existing pass laws were tightened up to control labour and the movement of black people. These laws needed to be challenged and resisted. O.R. decided to study law by correspondence, through Unisa, while continuing his teaching. After serving his articles he qualified, then in 1952 joined Nelson Mandela to start an immensely successful firm of attorneys, dedicated to assisting black people against the oppressive apartheid legislation.

Chief Albert Luthuli was elected President thousands of people. It also resulted in a spate of banning orders for its leaders. After Walter Sisulu was banned, Oliver Tambo became national secretary. He and Chief Lutuli, highly respected for his refusal to be ‘bought off as a chief by the apartheid regime, worked together on the ANC’s programme of mass campaigns and policy during the remainder of the decade. O.R. was deeply influenced by Luthuli’s simplicity and integrity.

The ANC is the parliament of the people’, Luthuli declared. In 1955, the Congress of the People presented to the nation the Freedom Charter, which reflected the grass roots demands of a democratic South Africa. O.R. was a member of the National Action Committee, which had drafted the clauses based on the popular vision. The following year, he, Luthuli, Mandela, Sisulu and 152 others were arrested for High Treason. But after the preliminary hearings, O.R. and Chief Luthuli were acquitted. In the meantime, with the bulk of the ANC leadership still on trial, Tambo and Luthuli had to continue to lead the struggle. During this period O.R. also updated the ANC constitution, presenting a more detailed, enlightened and inclusive vision, based on the ANC’s formal acceptance of the Freedom Charter.

There were some Africanists, within the ANC though, who had a problem with this broader all-encompassing definition of the nation. They were also unhappy with the formation of the ANC Alliance, which consisted of the South African Indian Congress, the South African Coloured People’s Organisation, the tiny white Congress of Democrats and the South African Congress of Trade Unions. They felt that the ‘non-African’ organisations might easily come to dominate the ANC. Eventually, after a noisy confrontation at a regional meeting in 1959, chaired by Oliver Tambo; they broke away to form the Pan Africanist Congress.

In 1957, Oliver had become engaged to Adelaide Tsukudu, a Youth League activist and qualified nurse who worked at Baragwaneth Hospital (now renamed the Baragwaneth-Chris Hani Hospital). The wedding date, set for December 1956, was nearly derailed, as the bridegroom was arrested for High Treason. Fortunately, all the accused were granted bail, and the marriage took place, followed by a joyous wedding reception – for who knew what the future might bring!

O.R. was destined to see very little of his family once he went into exile. Adelaide Tambo became the breadwinner, working double shifts to provide for their children, Thembi, Dali andTselane. She also made her home a place of refuge for ANC members arriving in the UK.

There is a danger in celebrating the lives of men, that we do not properly acknowledge the central role of the women who maintained the household, raised the family and enabled their husbands to play a leading role in the movement. The ANC owes a great debt to them. The photograph below shows Oliver Tambo in Denmark in 1963Historic events had taken place in the last couple of years. On 21 March, I960, police fired on a crowd of people who gathered outside the Sharepville police station to protest against passes. Sixty-nine people died on that day. The event unleashed a storm of protest both at home and abroad. Panicking, the apartheid government banned the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress, and declared a state of emergency, jailing thousands of activists. Chief Luthuli, mandated by the ANC’s executive, then instructed Tambo to leave the country to set up a Mission in Exile in order to gather international support for the liberation movement. Once they met O.K., the Scandinavian countries proved to be amongst the most supportive (together with the Netherlands) of the western countries. But it was not always plain sailing for the ANC. In the early period of the mission in exile, O.R. had to deal with many different countries with conflicting ideologies and policies. The governments of most western countries were unhappy with the ANC’s willingness to work with the SACP and also its turn to armed struggle in 1962. In Africa, the movement’s non-racial policy was seen as a drawback by many newly independent countries, which had fought against white colonialism. It was thanks to O.R.’s obviously genuine commitment, his insight, understanding and his ability to articulate the ANC vision, that negative images of the ANC were eventually dispelled. In 1962 O.R. and Mandela were delighted to meet again. Mandela left South Africa illegally to help O.R. and the mission to raise support for the movement, and to explain the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the movement’s armed wing to international supporters. Mandela then returned home, to continue his struggle inside South Africa underground.

O.R. campaigned ceaselessly for international sanctions against the apartheid regime. The ANC’s staunchest supporter was Father Trevor Huddleston, Oliver’s old friend from St Peter’s days. Dr Dadoo, leader of the SACP, was also particularly responsive to this economic weapon. The campaign grew to include the boycott of South African sports, arts, academic and all cultural interaction as well as South African export product.

After the arrest of the bulk of the ANC leadership, including Mandela, following Rivonia, the ANC was severely weakened internally. When Wilton Mkwayi was arrested and imprisoned, the position of Supreme Commander of MK was passed to O.R., in exile. The ANC set up its headquarters in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.That country’s head of state, Julius ‘Mwalimu’ Nyerere generously donated land for the use of MK as well as any other programmes necessary for the ANC.

It was at Morogoro, Tanzania, that the ANC was able to hold its first conference outside South Africa, in 1969.The conference was sanctioned by the leadership on Robben Island, and was O.R.’s constructive response to criticism by cadres who were itching to return home to wage the armed struggle inside.

Umkhonto we Sizwe cadres in training for the Luthuli Detachment’s first military battle against the combined forces of Vorster and Smith .in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), 1967. After the arrest of Nelson Mandela and Wilton Mkwayi, O.R. became Supreme Commander of M.K.

One of the leading protesters was Chris Ham, who had been jailed for two years in Botswana following the ambitious military campaign to invade South Africa via the hostile territory of Rhodesia, through Wankie. ‘I blew my top,’ Chris Hani remembered. While much of the leadership was furious -with Hani’s outburst and wanted to discipline him severely, it was O.R. who was able to overlook the provocation, and really listen to the points Hani was making. The outcome of the Morogoro conference was a significant step forward. Conference agreed that in future political interest was to take precedence over the military, and that a Revolutionary Council (RC) be formed to give direction. The non-racial composition of the RC, though, proved to be a problem with a small, Africanist group of middle-level membership. After many discussions with O.R., they were unable to come to terms with the inclusion of’non-Africans’ in the structures. Eventually, the Group of Eight, as they were called, broke away.

It was to the credit of O.R., and the general esteem with -which he was held, that the split was contained, and did not spread further. Tambo was, as so many exiles have confirmed, the ‘glue’ that held the movement together during the most difficult and frustrating years in exile.

O.R. immediately began to raise funds from the international community to give these children shelter and education. As a successful teacher himself, O.R. was most concerned that these young exiles should first complete their schooling before joining the military struggle. With the help of comrades, O.R. also initiated the Luthuli Foundation, which allocated bursaries to serious students, placing them in friendly countries around the world.

The massacre by the apartheid regime’s South African Defence Force (SADF) in Maseru, 1982, resulted in the deaths of 42 men, women and children, including 12 Basotho civilians. The bombing was part of a general destabilisation campaign on neighbouring countries which lent support to the ANC. Particularly threatening to South Africa was the sustenance the ANC received from socialist countries, including Cuba. The SADF embarked on a series of invasions into Angola, with the encouragement of the USA. It aimed both to drive out Cuban troops who had responded to the elected Angolan government’s call for assistance, as well as to smash the MK camps. A series of bombing attacks and pitched battles occurred. At Cuito Cuanavale, MK helped to defeat the SADF. This was an enormous psychological victory for MK. But from then onwards, the struggle began to escalate.

In response to the penetration of selected cadres into South Africa, the SADF unleashed a series of raids on neighbouring countries. These included the bombing of civilian as well as MK targets in Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Lesotho. Despite the very real threat to his life, O.R. unexpectedly appeared in Maseru – so dangerously close to South Africa’s borders – to attend the funeral, and to grieve along with the families and comrades of those who were massacred.

The almost unbearable strain began to affect the movement. The apartheid government sent an ultimatum to the neighbouring countries – expel the ANC, or more raids – would follow. The ANC was obliged to -withdraw from some countries. It was becoming clear that the liberation movement had been infiltrated by informers and askaris. Suspects were questioned, and a number found guilty. In some camps, frustration and uncertainty introduced a climate of suspicion, even paranoia. Prisoners took the brunt of the tension. Eventually, the maltreatment of these prisoners came to the attention of O.R.. He appointed a committee of investigation, and eventually the abuses were curtailed. The committee -was also instructed to formulate a Code of Conduct for both MK and the ANC. A Bill of Rights followed, so that this appalling relapse into inhumanity might never occur again.

O.R. was foremost amongst those who advocated rights for women in the movement. Today’s constitution is an acknowledgement of O.R.’s highlighting gender sensitivity in the ANC nearly fifteen years earlier. Perhaps one of his most well known speeches is remembered for its gentle humour as well as for the challenge it presented to both men and women in the ANC:

Women in the ANC should stop behaving as if there was no place for them above the level of certain categories of involvement. They have a duty to liberate us men from antique concepts and attitudes about the place and role of women in society and the development and direction of our revolutionary struggle. In fear of being a failure. Comrade Lindiwe Mabuza cried and sobbed and ultimately collapsed on top of herself when she learnt she bad been appointed ANC Chief Representative to the Scandinavian countries. But, looking at the record, could any man have done-better?’ – O.R.Tambo’s speech to the Women’s Section of the ANC, Luanda, Angola, 1981.

O.R. was always supremely aware of the value of spelling out clearly the policy of the movement, both to conscientise its members as well as to provide clear guidelines to its representatives in difficult situations. The ANC formally subscribed to the Geneva protocols. It also again revised and updated its constitution. In the preparations for the changes, O.R. made extensive contributions to the guidelines for the commission on the constitution. In the ANC’s Bill of Rights, O.R. was also instrumental in foregrounding children’s rights, and firmly declared a principled tolerance of sexual orientation.

Looking ahead, O.R made a firm policy statement on the necessity for a multi-party democracy after liberation, in which there would be freedom of speech, of assembly, of association, language and religion. This was an alternative to the one-party state model adopted by many independent African countries.

As mass resistance to so-called apartheid ‘reforms’ inside South Africa escalated in the 1980s, O.R. broadcast regularly on Radio Freedom. He called for a People’s War against apartheid. The democratic labour movement civic organisations, the National Education Crisis Committee, women and youth groups and other anti-apartheid organisations banded together to form the United Democratic Front. O.R. urged them to make the apartheid system ungovernable. State violence rapidly increased in order to suppress popular resistance to apartheid ‘reforms’ such as tricameral parliament, which consisted of whites, Coloureds and Indians only, and the new dummy local councils in the townships. Assassinations, tortures, deaths in detention, troops in the townships, and mounting anger.

At the ANC conference held in Kabwe in 1985, a sober assessment of the ‘structural violence of apartheid’ led to a decision to step up the armed struggle. O.R. continued to maintain the moral high ground, emphasising that civilian loss of life was still to be avoided. But henceforth military personnel and military officials would no longer be excluded in sabotage attempts. Nevertheless, O.R. did not attempt to deny, or ‘sanitize’ mistakes. A car bomb aimed at a military target but which killed four civilians was ‘inexcusably careless’. He pointed out though, that the violence of apartheid was the cause of these incursions in the first place, At the Children’s Conference held in Harare in 1987, to gather evidence on the widespread imprisonment of children, O.R. denounced the grisly method of necklacing. On behalf of the ANC leadership, he called on guerrillas to set an example by avoiding civilian casualties.

The economic weapon continued to be a major campaign. O.R.’s years of patient diplomacy and warm relations with anti-apartheid movements in western Europe and north America began to pay off. Sanctions and divestment campaigns amongst students, the churches, the African-American community, the trade unions and other progressive organisations in civil society were widely publicised, putting pressure on conservative governments to act against apartheid. Fund-raising campaigns and concerts reached a wide range of the population. Almost reluctantly, the Reagan and the Thatcher governments in the USA and the UK began to seek audience with the ANC leadership – they could no longer ignore the powerful popular support that the ANC enjoyed in South Africa, or indeed the widespread symbol that the movement had become, against the scourge of racism which existed throughout the world.

Similarly at home, more and more groups of people – Afrikaner intellectuals, various professionals, white trade unionists, sporting representatives and delegations from a variety of organisations – began to make the pilgrimage to the ANC’s headquarters in Lusaka.

During the turbulent eighties, the war on many fronts also included the issue raised by O.R. early in 1985 – that of talks with the enemy. He had outlined the necessary conditions to enable negotiations to take place; firstly, he said, a clear mandate would be necessary from the ANC inside the country; secondly, the prospect of talks. But he also firmly and publicly rejected PW Botha’s offer, made in parliament, to release Mandela provided he renounced violence. Lest there be doubts about his intentions, Madiba wrote a speech which his daughter Zindzi read out to an excited public gathering at Jabulani stadium in Orlando, Soweto:

In 1985, following PW Botha’s offer to release Nelson Mandela provided he renounced violence, Zindzi Mandela read her father’s speech at Jabulani stadium, in Soweto, ‘I am a member of the African National Congress. I bare always been a member of the African National Congress and I will remain a member of the African National Congress until the day I die. Oliver Tambo is more than a brother to me. He is my greatest friend and comrade for nearly fifty years. If there is one amongst you who cherishes my freedom, Oliver Tambo cherishes it more, and I know that he would give his life to set me free.

‘ Echoing his comrade Oliver Tambo.’s sentiments, he went on:

Let [Botha] renounce violence. Let him say that be will dismantle apartheid. Let him unban the people’s organisation, the African National Congress. Let him free all who have been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid. Let him guarantee free political activity so that people may decide who will govern them.

Once the possibility of negotiations became more likely, it fell on the ANC in exile to present the ANC’s strategy for negotiations to its members and to the world. Under Tambo’s guidance, a team prepared the Harare Declaration. The schedule was gruelling. As always, O.R. worked late into the night finalising the document, which required careful explanation. In the previous few years, his health had been visibly taxing him. In 1982 he had suffered a mild stroke, and his medical advisers pleaded with him to ease up on his work. Instead, he pledged to the movement that he would continue to work ceaselessly for freedom until the day he died. On 9 August 1989, as the delegation returned from its intensive presentations of the Harare Declaration, O.R. collapsed. He was rushed by plane, arranged by President Kenneth Kaunda, from Lusaka to London. He had suffered a severe stroke.

While O.R. lay in hospital, events occurred in quick succession. Within a few months, the ANC was unbanned and Mandela and other leading political prisoners released. As soon as he could, Mandela journeyed to Sweden, where O.R. was recuperating, to meet his old friend, after nearly thirty years’ separation.

Though we had been apart for all the years that I was in prison, Oliver was never far from my thoughts. In many ways, even though we were separated, I kept up a life-long conversation with him in my head.

Their reunion was joyous.

When we met we were like two young boys in the veld, who drew strength from our love for each other.

In December 1990, Tambo returned home. At the first Congress inside South Africa since then banning of the ANC, he reported on the mission, which he had been mandated, to undertake. He was able to deliver the ANC, united and successful. Many years had passed, entailing much pain, sacrifice and the loss of many lives, but the movement’s major principles remained intact. At the congress, Mandela was elected President of the ANC, with Oliver Tambo as National Chairman.

In his remaining three years back home, O.R. delighted in spending time at his sisters’ homestead in Kantolo, gazing at the mountains. Years earlier, in exile, he had longed to see that faraway, everpresent landscape of his childhood again. The mountain range, he said, had a special significance for him.

‘Looking out from my home, the site of it commanded a wide view of the terrain as it swept from the vicinity of my home and stretched away as far the eye could see – the panorama bordered on a high range of mountains that were faced looking out from home. The Engeli Mountains were a huge wall that rolls in the distance to mark the end of very broken landscape, landscape of great variety and, looking back now, I would say of great beauty… But the nagging question was, what lay beyond the Engeli Mountains? Just exactly what was there?… How far would one be able to walk over the mountains to Egoli, Johannesburg? What sort of world would it be?…What did it conceal from my view? I saw two worlds. The one in the vicinity of my home… This was my world. I understood it from my mother’s rondavel… I was part of this world. There was obviously another one beyond the Engele Mountains’.

In the early hours of 23 April 1993, Oliver Tambo suffered a massive, fatal stroke. His death came a mere two weeks after the murder of one of his most talented apprentices, Chris Hani.The shock of the assassination, as well as the very real threat of national mayhem narrowly averted, may well have hastened his own demise.

Oliver Tambo was accorded a state funeral. Scores of friends and heads of state from the international community – east, west and non-aligned – journeyed to bid him farewell. Oliver Tambo, after many years of toil and conscientious care, had led his people, like Moses, to the top of the mountain range. He did not live to see the other side.

Precisely a year after his death, the South African nation went to the polls in the first-ever democratic election. The African National Congress won an overwhelming victory. The people of South Africa had cast their vote of confidence in the ANC, and in the legacy that its leaders had imprinted on its vision. This was the moment for which Oliver Tambo willingly gave his life.

The first, hectic five years of democratic government have tended to overshadow the role of Oliver Tambo. Without him, and his close collaborator Nelson Mandela, the revolution might well have gone ahead, but it would not have taken the form that it did. Working closely with his comrades in exile, at home and on Robben Island, employing the time-honoured style of consensus and collective ownership of decisions. Tambo became the interpreter of the revolution – its teacher, its moral guide and its mediator. Oliver Tambo’s ideas live on in our constitution, in the democratic and cooperative values of the African National Congress and in its vision for a just, inclusive and equitable society. At a time when we are taking stock, and preparing for the next phase of our history, it is important to reflect on our heritage and pay tribute to Oliver Tambo, revolutionary thinker, humanist and mentor.

It is our responsibility to break down barriers of division and create a country where there will be neither whites nor blacks, just South Africans, free and united in diversity.